Recent statements from the US government announcing the expansion of the “Clean Network” raises concern about the growing arms race between two prominent leaders in Internet technology, US and China. Furthermore, the recent introduction of the Hong Kong Security law has raised alarm all over the world regarding Internet freedom and privacy in the region.

In this report, we show that the US government and military websites already have implemented new technical measures to drop traffic from Chinese IP-prefixes, blocking access to more than 50 websites. Interestingly, we also found that these policies are applied to Hong Kong (until recently considered a country with a comparatively “Free” Internet), exacerbating concerns about the shift in attitude in the Internet space surrounding users in Hong Kong.

Although this kind of geoblocking is frequently employed to safeguard websites against malicious attacks, previous studies have found that overblocking contributes to the overall “balkanization” of the Internet, where users from different regions have access to vastly different online experiences. We fear that the opaque implementation of such geoblocking forebodes the start of a slippery slope that could lead to a highly fragmented Internet.

Background:

In late June ‘20, a WSJ reporter reached out to Censored Planet and presented us with a list of 59 US government and military websites that appeared to be blocked in Hong Kong. Asked to analyze this phenomenon in depth, we set out to explore the following research questions:

- What US Government and Military websites are inaccessible from Hong Kong but are available from other countries?

- Who is doing the blocking and how is it implemented?

- Is the blocking similar to access patterns from neighboring China?

High-level takeaways

- Out of 59 US Government and military domains tested, only 6 domains are directly accessible from multiple vantage points in Hong Kong. The other domains employ some form of blocking performed by server-side towards Hong Kong IP prefixes.

- 49 domains are blocked by DNS-based geoblocking i.e. the DNS resolution fails if the DNS resolver performing the recursive resolution is located in Hong Kong.

- We discovered that a set of 6 .mil DNS nameservers (e.g. con2.nipr.mil) prevent requests from Hong Kong, thereby restricting access to 37 .mil domains. In the case of 12 .gov domains, other nameservers were doing the geoblocking.

- Although DNS-based geoblocking can be easily circumvented by using a DNS resolver outside Hong Kong, we find that some domains further restrict TCP connections (17-20 domains) or HTTP connections (4-6 domains), indicating the deliberate steps taken by these sites to restrict access.

- We performed similar measurements from China and observed the same blocking behavior, indicating that these domains have the same policy for both China and Hong Kong.

Measurements and Results

Test List:

Our test list consisted of 59 unique domains, all affiliated with the US Government or US military. Of the 59 domains, 37 were .mil (such as eucom.mil), 20 were .gov (such as census.gov) and 2 were .org (ndi.org and www.huduser.org).

Vantage Points:

We obtained access to one datacenter network and two commercial VPN server networks in Hong Kong. We verified using multiple IP to geolocation databases (MaxMind, IP2Location, ipinfo.io, DB-IP) and traceroutes that our vantage points are geolocated to Hong Kong.

Control Tests:

Before starting our measurements from Hong Kong, we performed control measurements (DNS resolution, TCP handshake, and HTTP GET request for all domains) from control datacenter vantage points in the US, UK, and Germany. All the domains resolved successfully and were accessible. We collected all of the DNS resolution responses for use later in our geoblocking tests from Hong Kong.

Geoblocking tests in Hong Kong

We performed geoblocking tests on 3 different protocols - DNS, TCP/IP and HTTPS.

-

DNS tests:

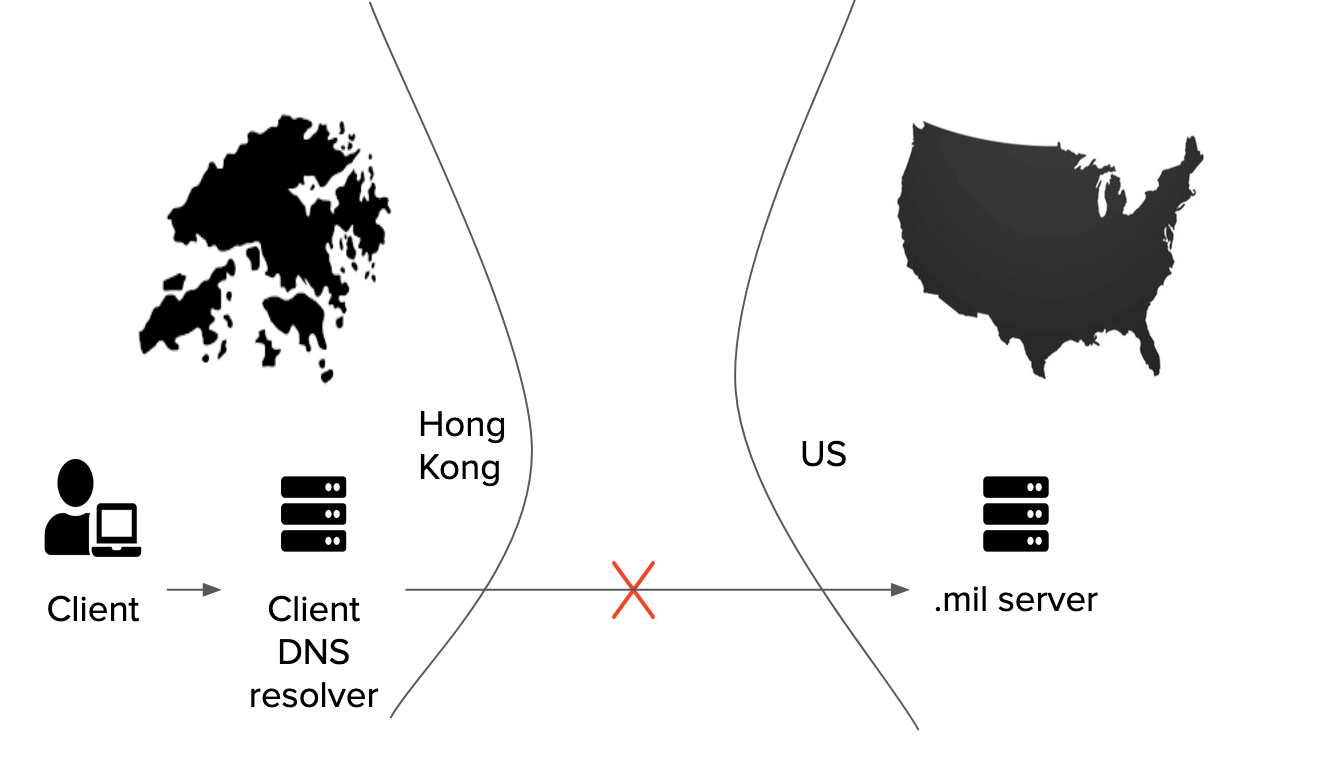

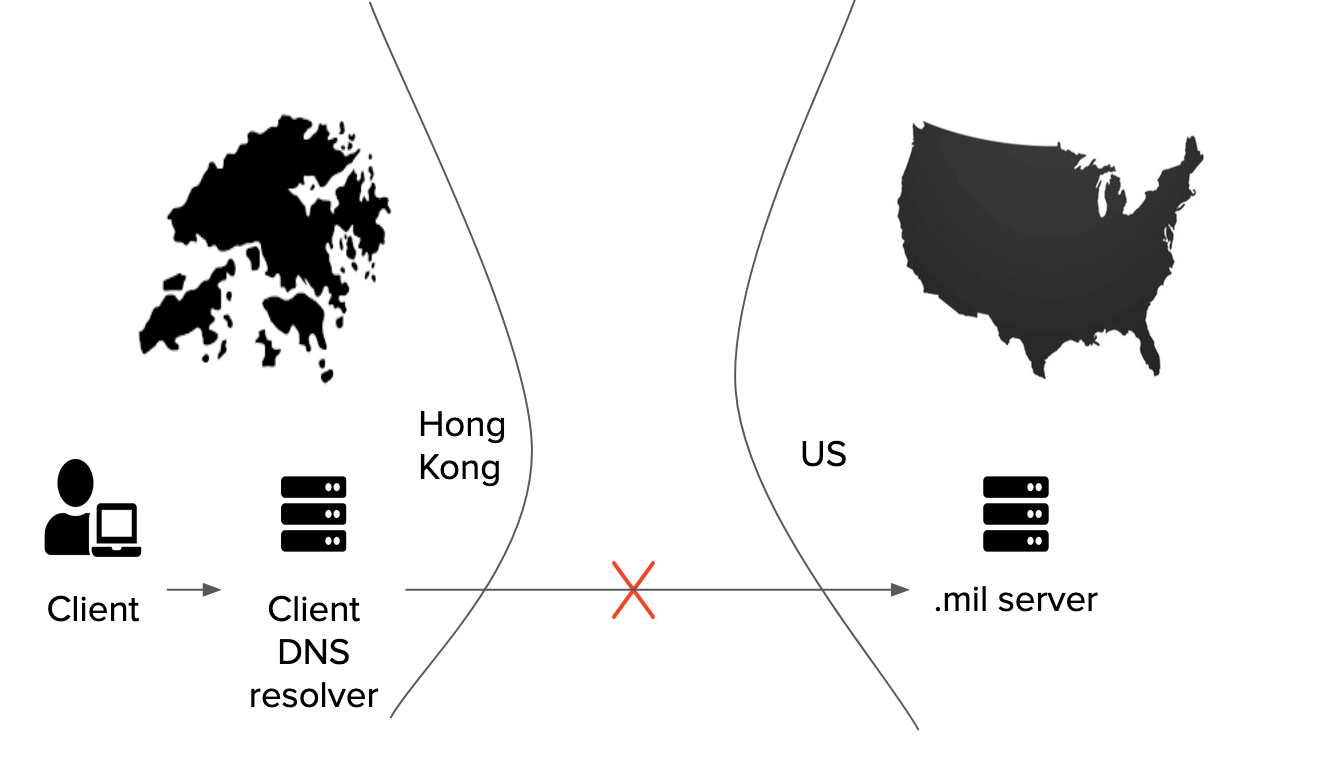

We performed DNS resolutions for all the 59 domains using local resolvers from each of our Hong Kong vantage points. For 49 domains, the DNS queries from all of our vantage points received an error response (SERVFAIL). For the other 10 domains, we received a routable IP address: 6 of these domains successfully returned the content while the other 4 returned a 403 Forbidden page.

Next, we performed DNS resolutions using Cloudflare (1.1.1.1) and Google (8.8.8.8) as the DNS resolver and we observed that the result was similar to using a local resolver. Our traces indicated that the point of presence of Cloudflare and Google DNS resolvers were located inside Hong Kong, thus still being affected by geoblocking.

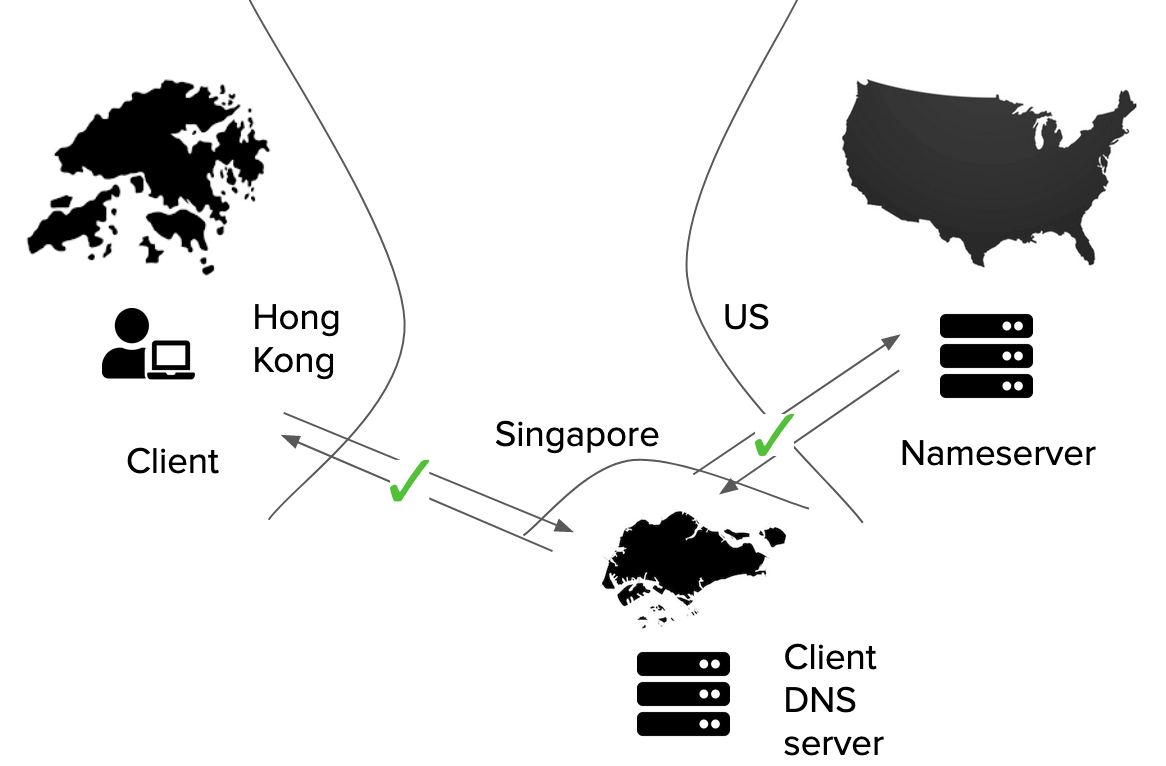

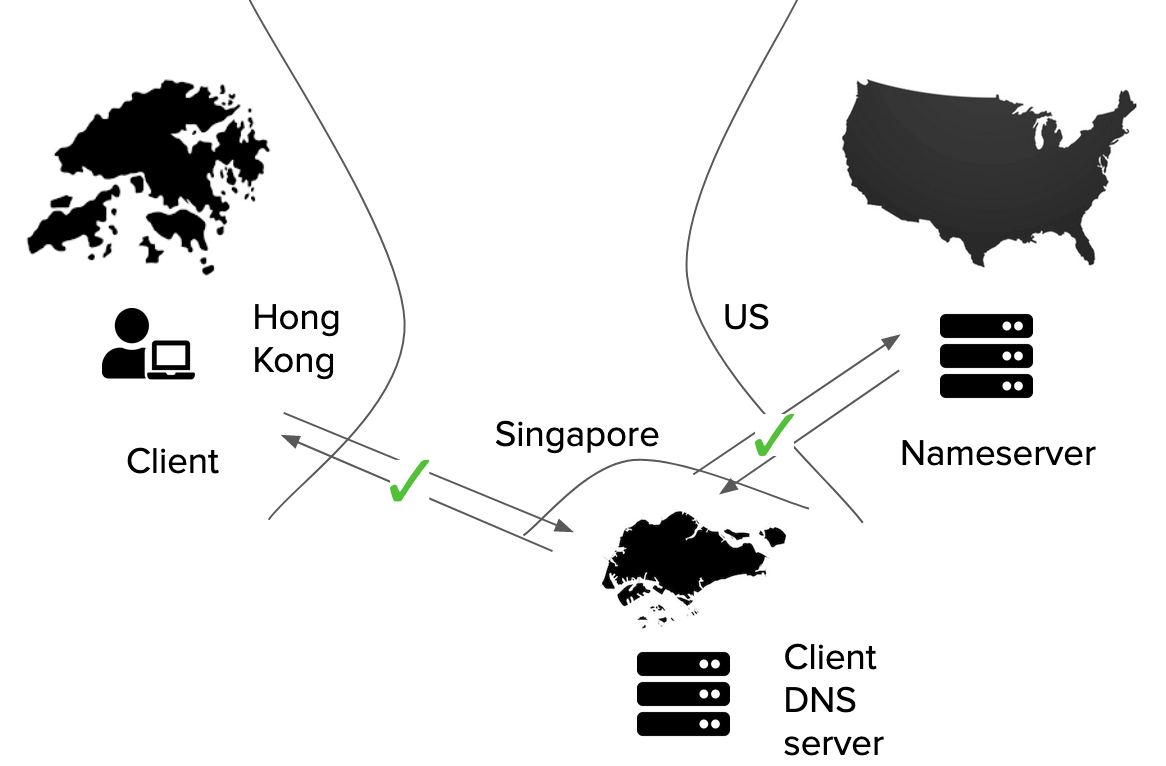

We next performed resolutions using a DNS resolver outside Hong Kong (e.g. 9.9.9.9, the Quad9 resolver located in Singapore). We observed that these measurements resolved successfully for 56 domains.

Additionally, we observed that DNS requests originating from a US client but with a DNS resolver in Hong Kong were also blocked.

All of these measurements indicate that the DNS blocking is only happening for requests from DNS resolvers in Hong Kong, indicating DNS resolver performs geoblocking.

We looked into each step of DNS resolution and observed that for all of the 37 .mil domains, the resolution fails when requests are sent to a set of 6 nameservers in the DNS chain: con2.nipr.mil, eur1.nipr.mil, eur2.nipr.mil, pac2.nipr.mil, con1.nipr.mil, pac1.nipr.mil. The nameservers that were failing for .gov domains were varied. This includes nameservers such as ns2.dol.gov and dns02.cns.gov.

DNS-based geoblocking is an effective way to restrict access to a large number of related domains, since it can be effortlessly applied by a set of nameservers higher in the resolution chain without any engagement from each of the individual authoritative nameservers.

However, it can be easily circumvented by obtaining the correct IP or using a DNS resolver outside Hong Kong. To this end, we collected all the IP responses obtained from our control measurements, and performed our TCP/IP and HTTPS tests.

-

TCP tests:

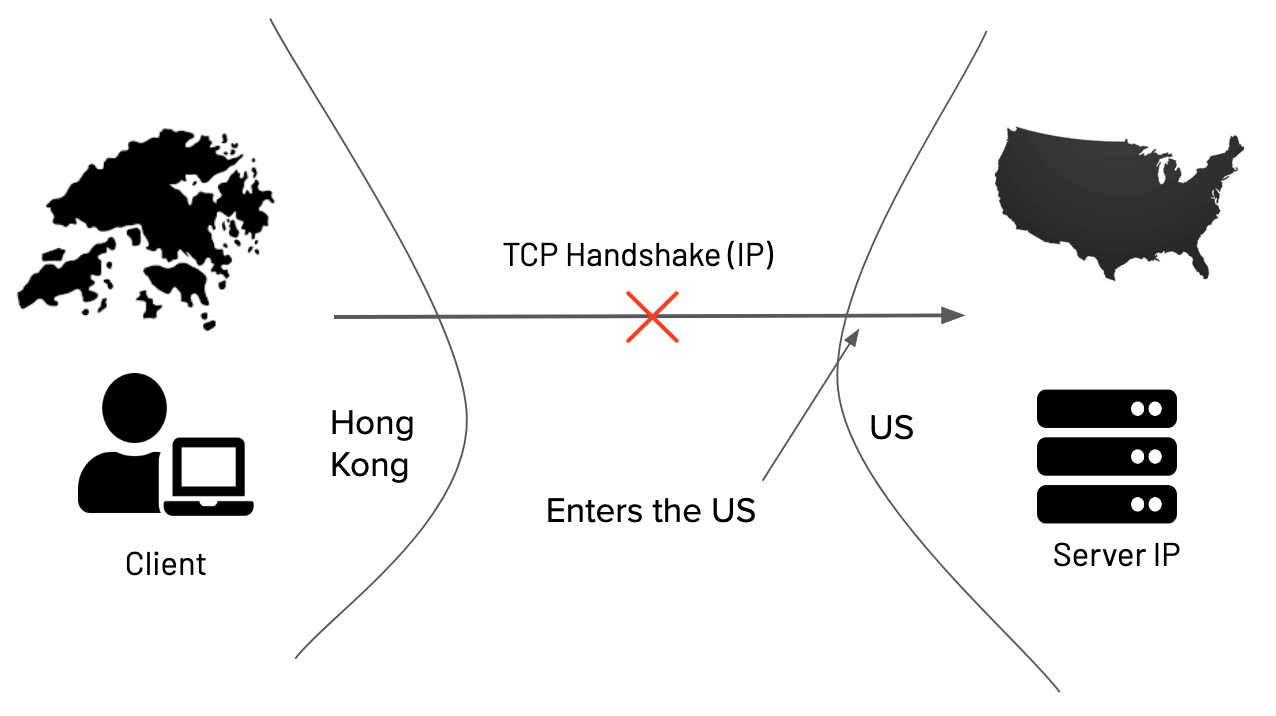

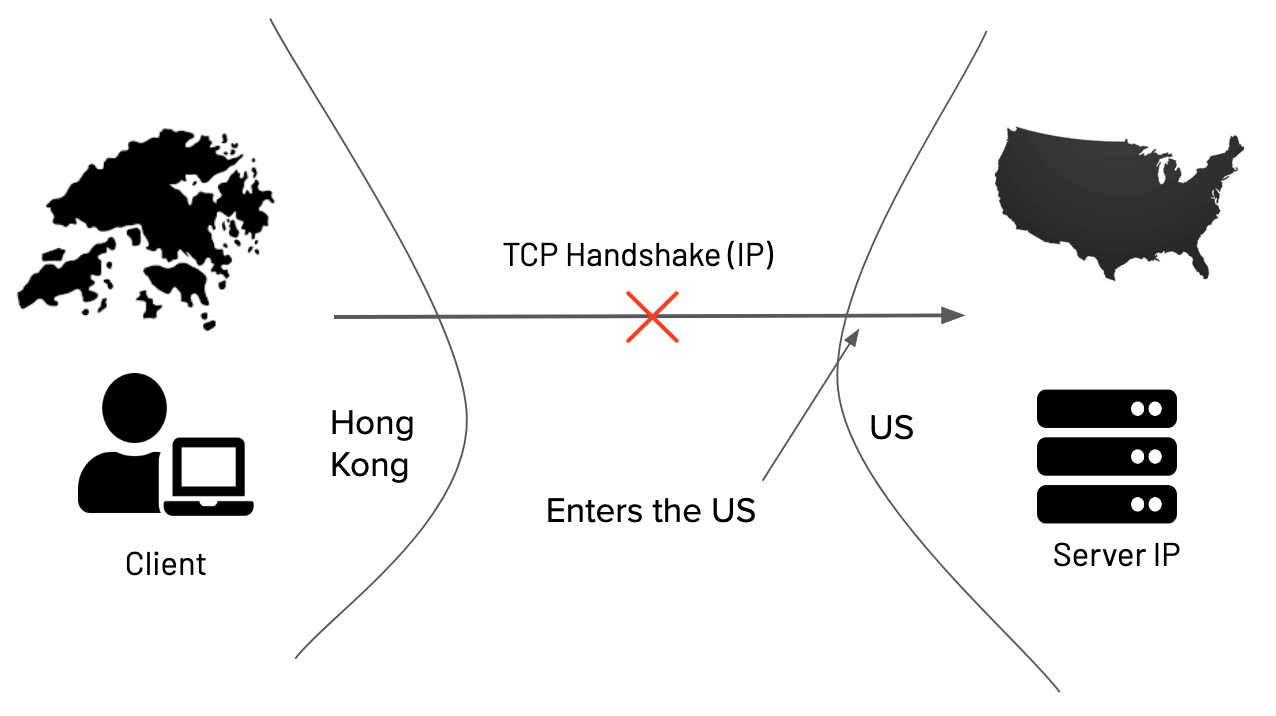

We performed TCP handshakes for all of the IPs resolved from the control measurements for our 59 domains. We observed that around 17-20 domains did not respond to TCP handshakes. To rule out censorship and observe where the blocking is implemented, we performed TCP traceroutes to the IPs, and observed that the connections entered the US before timing out. An example traceroute is shown here. This shows that, in addition to DNS-based geoblocking, many domains employ additional IP-based geoblocking for clients from Hong Kong, showing the desire of website administrators to stop any access from Hong Kong.

Again, we observe that proxying the connection through another country successfully establishes the TCP handshake.

-

HTTPS tests:

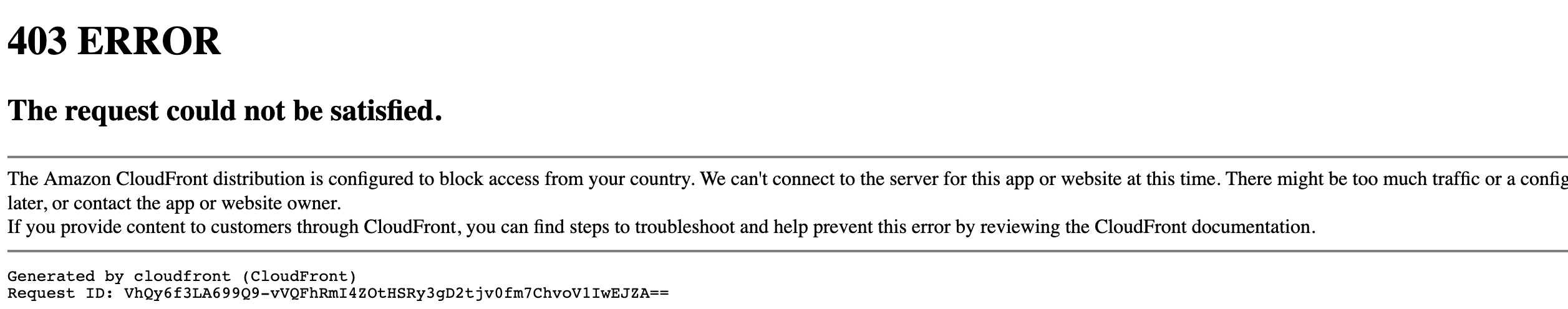

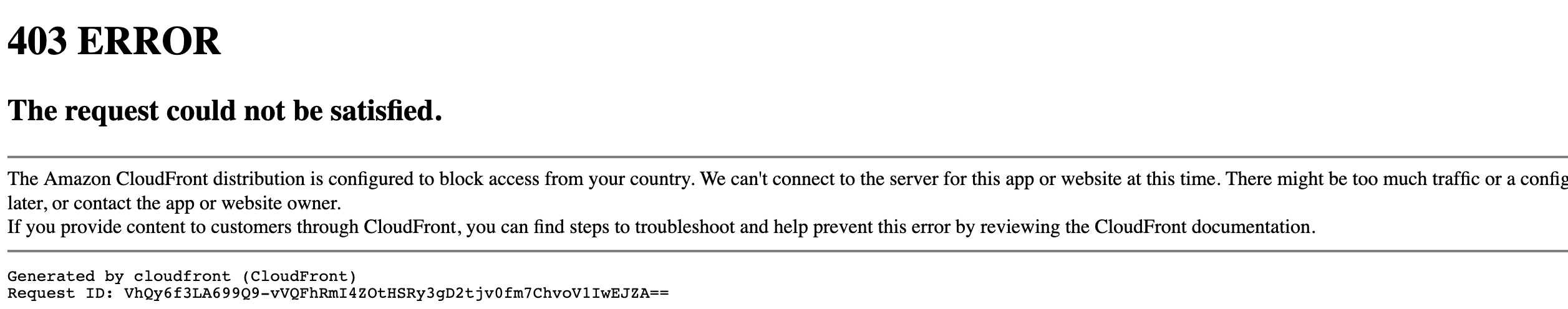

We performed HTTPS GET requests to all the Domain-IP Address pairs that we could establish a TCP handshake (39 - 42 domains) and checked the responses for any geoblocking errors. We observed that 4 domains returned HTML responses that showed clear signs of geoblocking from all of our vantage points: stats.bls.gov, www.census.gov, www.jobcorps.gov, www.sss.gov. Additionally, 2 domains (www.navy.mil and www.usmc.mil) responded with geoblock pages for measurements from one of our VPN networks. An example blockpage for www.sss.gov is shown below:

The page, hosted on Amazon CloudFront, one of the most popular CDN networks, indicates that the blocking is based on the location of access.

Accounting for all the different types of geoblocking, only 6 domains are directly accessible from Hong Kong from our test list of 59 domains: www.cao.gov, www.chcoc.gov, www.huduser.org, www.ndi.org, www.osmre.gov, www.swpa.gov.

Geoblocking tests in China

We performed the same tests from a datacenter network in China to observe whether there is a common policy for US Government and Military domains for both Hong Kong and China.

For our DNS measurements, we observed errors for the same 49 domains as in Hong Kong. After providing the correct IP, we observed that 19 domains were geoblocked at the TCP handshake level, and 6 domains showed signs of geoblocking when HTTPS requests were performed. The results are very similar to Hong Kong, indicating the similarity in policy.

Conclusion

We fear that such inclination from the US Government to geoblock certain parts of the world (and not others) sets a dangerous precedent for open communication in the Internet - a concern that is exacerbated by the recent “Clean Network” announcements. Moreover, Hong Kong’s new security law, which mandates ISP surveillance and censorship, may lead to a volatile Internet space subject to very stringent policies not only from China, but from other countries now viewing Hong Kong as a security threat. Previous studies have shown the feasibility of using policy and law to implement effective Internet censorship, and the same may be true for Hong Kong in the coming months. We are actively monitoring this change, and collecting data that can bring more transparency to this draconian policy.